A visit to West Midlands Police Museum

By Pete James, independent photographic historian and curator

Earlier this month I had the opportunity to fulfill a long-held ambition – I finally got to see the collodion positive portraits of criminals in the West Midlands Police Museum.

The opportunity to view these amazing objects came through an invitation to deliver a talk in response to Ikon’s current exhibitions; Edmund Clark’s In Place of Hate and a historical exhibition by 19th Century convict artist Thomas Bock. Both contain portraits which explore identity, surveillance and representation. Clark’s exhibition includes a series of large scale diffused portraits of staff and those in custody at HMP Grendon projected onto prison bedsheets and the Thomas Bock show includes pencil sketches of a convict executed for murder made in 1824 and daguerreotype portraits made in the 1850s. The Birmingham police photographs seemed to offer the perfect way to do something which somehow responded to both bodies of work and created greater public awareness of some very important local photo-historical material.

I first became aware of their existence through John Tagg’s essay, The Burden of Representation: Photography and the Growth of the State, published in a special edition of the quarterly photographic journal Ten. 8 (No 14). This special edition of the journal, titled Consent and Control, was devoted to a series of essays about photography and surveillance. Although over thirty years old, it is still worth checking out – as are all the other editions. Tagg had previously published the photographs of Birmingham prisoners in an essay Power and Photography, in Screen Education, Autumn 1983.

The police photographs lived in two parallel worlds for me; as noted examples of the way in which the seemingly objective vision of the camera had been employed as a tool of surveillance and control in the nineteenth century and as evidence of a critical moment in the history of photography in Birmingham. They had captivated my imagination for almost three decades.

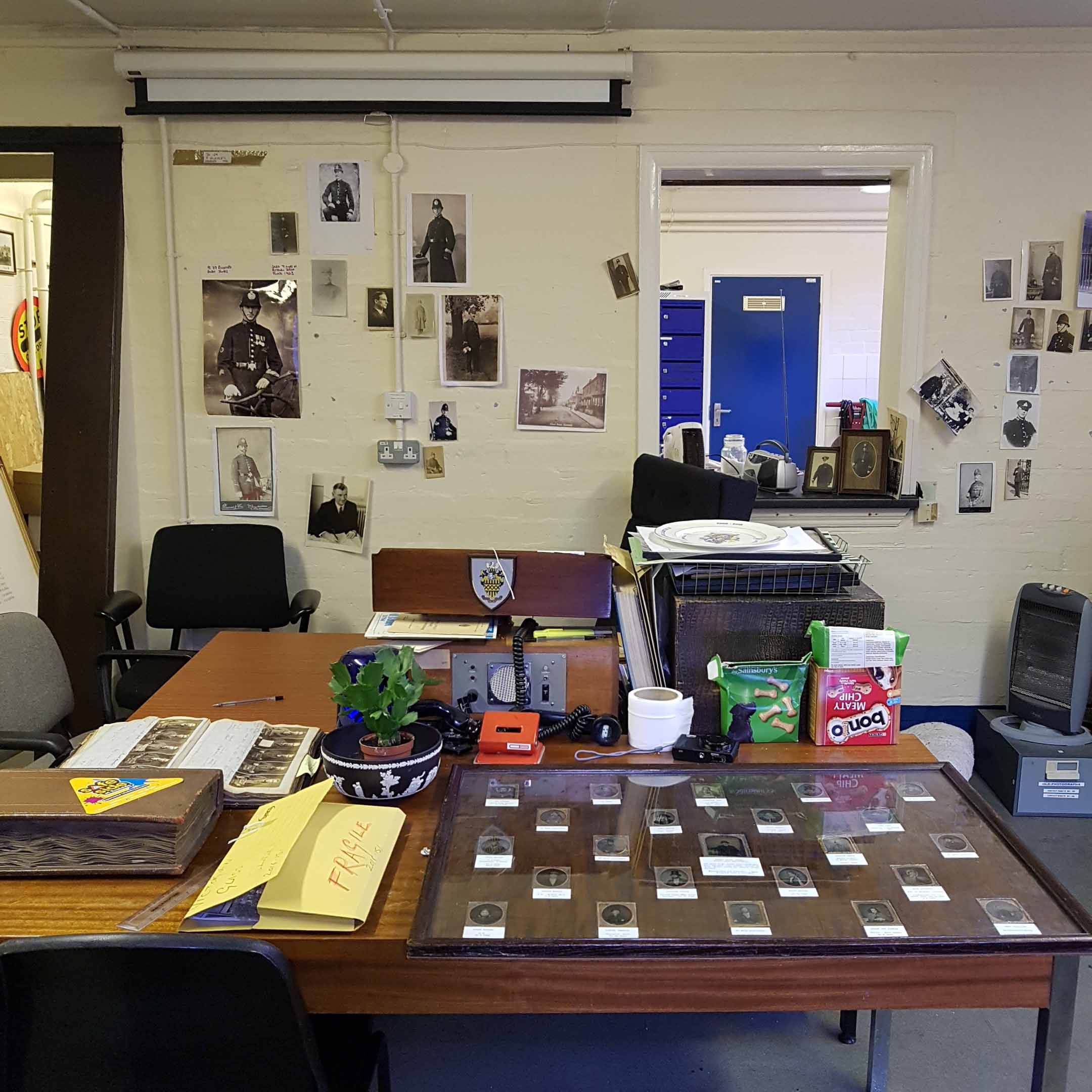

Corrine Brazier from the West Midlands Police Heritage Project met Ikon’s Kerry Hawkes and I at Sparkhill Police Station. This now houses the Birmingham Police Museum, an extraordinary collection of material spanning the entire history of Birmingham’s police. Having been on display at Tally-Ho Police Centre and then moved to Sparkhill, the collection is currently being cataloged and packed up by a team of dedicated volunteers with a view to it moving to a new permanent home, the Steelhouse Lane Lock-up, where it can be shown to its best advantage.

Passing through a huge iron door, we entered a cluttered room and there, laid out on a table, neatly mounted and captioned in a wooden frame, were twenty-three collodion positive portraits. Corinne then showed us three more loose portraits. Pause, deep inhalation of breath. After all these years I could finally look, (carefully) touch and explore these extraordinary images, made over 150 years ago in a commercial portrait studio in Moor Street

Police Museum, Sparkhill

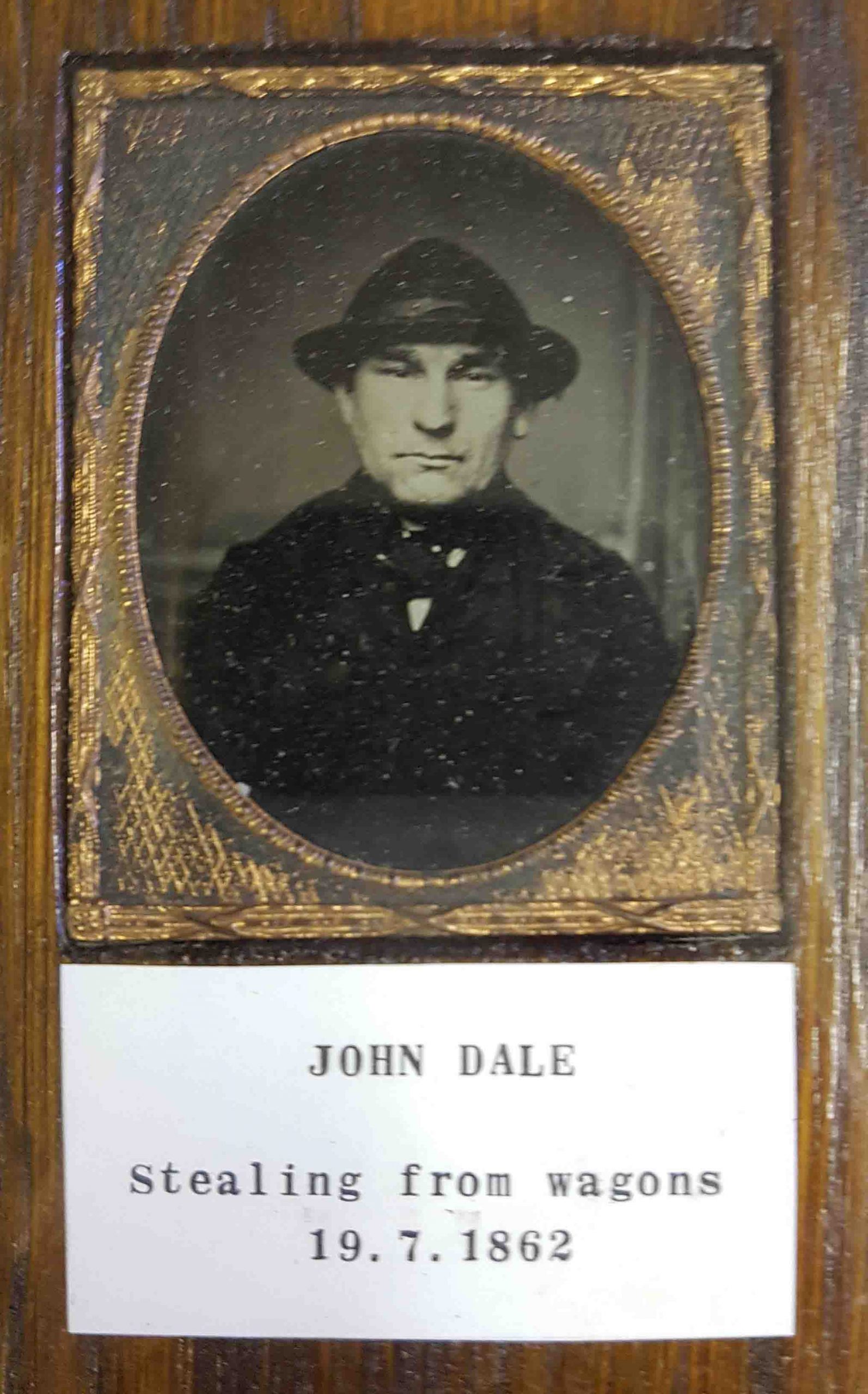

At first sight, were it not for their labels, it might perhaps be hard to distinguish some of these portraits from those made by paying customers at William Eagle’s studio. Set behind protective glass covers and surrounded by a moulded pinchbeck frame, the faces of the male and female culprits of a diverse range of crimes loom out of the darkness. Some posed in a seemingly casual manner, sitting formally in studio settings with hand painted backdrops. Others stare out from tighter compositions taken against the more functional backdrop of a brick wall. Each and every one has an amazing story to tell.

John Dale, Stealing from wagons, 1862

On the adjoining table was an album, the Record Book for 1877. This contains page after page of small, carte de visite size portraits pasted in rows above scrawly notes which document their names, crimes, punishments and the negative numbers through which they could be traced in the photographer’s archive. Each sitter awkwardly holds or has a chalk board suspended around heir neck upon which details of their name and reference numbers have neatly been written. Unlike the collodion positive portraits, each sitter occupies roughly the same space within the frame and are photographed against a neutral background revealing the development of a more systemised practise of documentation. Some frown, some stare, some look away. Others confront us with a defiant glare but it is perhaps the photographs of the young boys which stick in your mind. Each and everyone of them looks anxious as they wait for the plate to be exposed, their likeness to be imprinted on it and to be led away to serve their time.

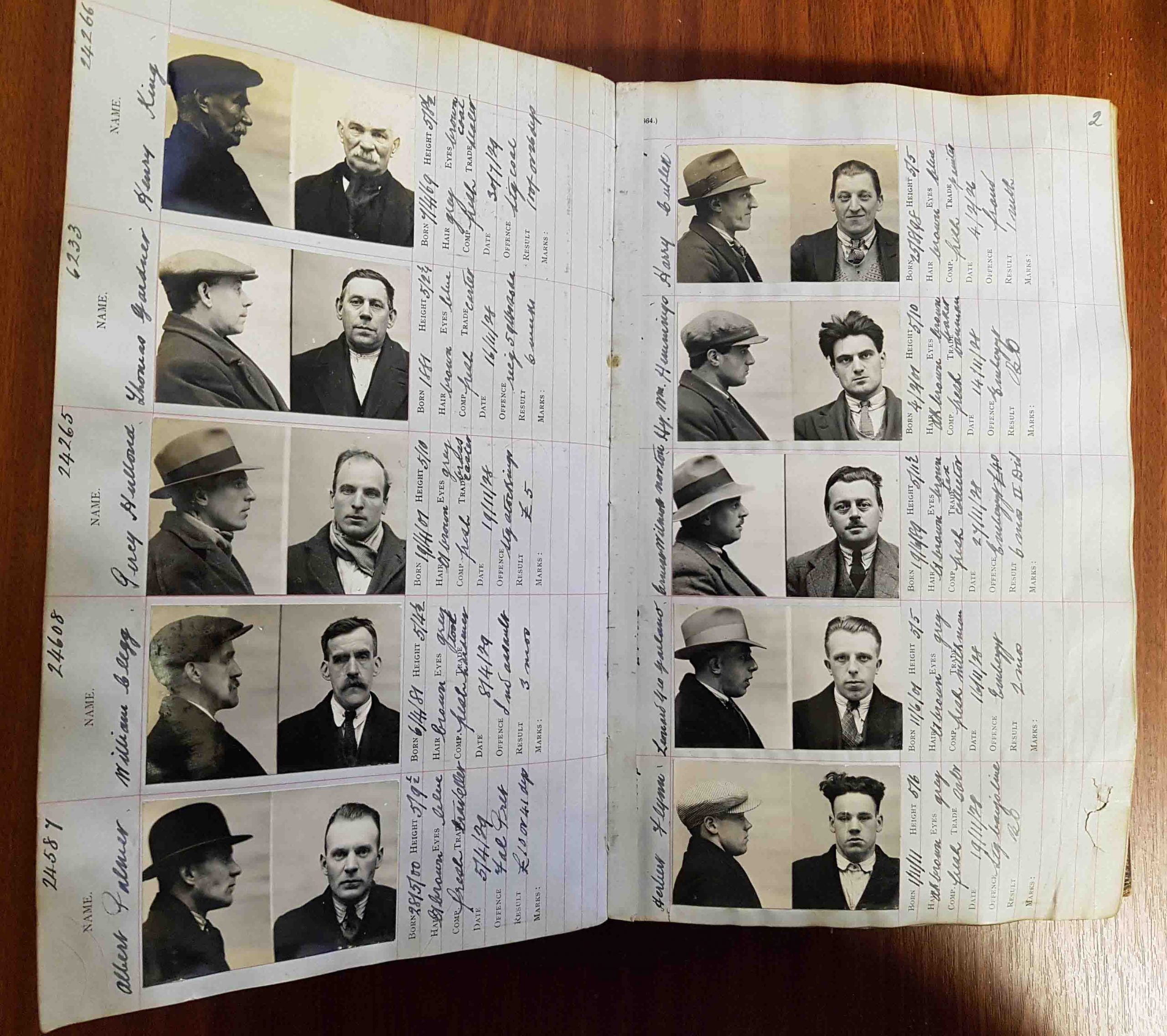

Male First Offenders

Sitting alongside was another album of later silver prints. Identified as ‘Male First Offenders’ by gold embossed lettering on the spine, this album holds prints pasted onto specially printed pages which document name, date of birth, the colour of eyes and hair, height, company, trade, date, offence and ‘result’. This extraordinary cast of characters from the underbelly of Birmingham life in the 1920s and 30s reveals a hidden world captured elsewhere in the archive in ‘scene of crime’ photos. Photographed from the front and side, hat on and hat off, here again there’s a complete range of expressions from fear to smiles, of defiance and submission to the law.

Having pored over images spanning almost 100 years of police photography, I had the opportunity to view another part of the museum. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted Victorian camera, a chair, and a board in a huge display case. Pause for breath a second time. I’m hoping to return for a closer look to glean some more information on this amazing piece of photographic and police history.

The Police Museum is an extraordinary historical and cultural resource that should be on public display in the city. Hopefully, the fundraising efforts of Corinne and her colleagues will enable this to happen so everyone can have the opportunity to see these amazing historical objects.

Pete James is an independent photographic historian and curator. He is Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Digital Humanities at the University of Birmingham. He is currently researching George Shaw (1818-1904), Birmingham’s first photographer.